After toiling for years in the minefield of nonprofit agencies, the courts, the juvenile justice system, schools, and community mental health, I eventually forayed into the land of private practice. I had been primarily trained as an infant mental health (IMH) specialist but had done some supervised play therapy training and work earlier in my career. I knew the chances of building a practice of solely IMH work was remote, so I began seeing families with young children for parent-child play therapy as well. I had a vague awareness that I had rarely worked with families that were “good enough,” where the children were sturdy and competent, unhindered by histories of loss or trauma and where parents had the psychological and material resources to meet their children’s needs. I had worked with abused and neglected children for so long that I had forgotten, if I ever knew, what a “typically developing” child—even one who was struggling emotionally for some reason—acted like.

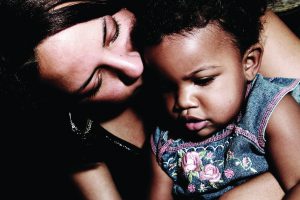

As I began to work with “voluntary” adoptive and foster families, often self-referred, I began to hear stories not unlike the ones I had heard in prior years. Parents came to me confused as to why, when trying to do things differently with their own child than had been done with them, or to love a child who felt himself to be unlovable, they were finding themselves exhausted, angry, overwhelmed and sometimes feeling helpless. I came to see that the issues these families faced were not so different from the issues faced by families I had worked with in the past, just buffered, more often than not, by less preoccupation with the provision of concrete needs. The differences in coping and in support was, nonetheless, profound. Whereas in the past, I had seen a predominance of families where the family had become “possessed by their ghosts,” now I was seeing more families where the ghosts were “transient…who [did] their mischief according to a historical or topical agenda.”1 I felt a sense of relief when I encountered parents who could describe their child with some measure of depth, who could differentiate their experience of an event as distinct from their child’s, who could express ambivalence about their ideas about parenting and who could assume some measure of responsibility for the nature of the relationship with their child. Of course, I had encountered parents such as these in the child welfare system, but often, by the time families received services, they were depleted of goodwill toward their child and the stable, loving feelings that so often protect a child during times of stress was worn thin, if ever present. In this new private practice environment, even families that were referred from child welfare or their pediatrician were coming with some measure of hope and optimism. It made all the difference.

As time went on, I was referred an increasing number of intact, biological families. This was a completely new game. Without the evident history of abuse, loss, neglect or abandonment implied by involvement in the child welfare or adoption system, I was on my own, so to speak, to discern the nature of the ghost…transient or possessive? Tenacious or permeable? How I would help families identify and say goodbye to their ghosts? It was a different kind of challenge. Sometimes, I was referred an “easy” family. Clair was from such a family. Bright, vivacious and expressive at 3.5 years old, four weeks earlier Clair had been bitten in the face by the beloved family dog, Rex, who then “disappeared.” Clair’s parents, Mark and Emily, called for services after the childcare staff noted Clair had suddenly and increasingly become terrified of spiders and ants, such that she was now resisting going outside with the rest of the children during playground time. I saw the parents alone for an intake interview. Though clearly concerned about their daughter, they both presented with an air of ease, freely conversing and openly thinking about their and Clair’s experience in a rich and coherent way. Emotions evident in the intake included their concern for their daughter, the worry and guilt they were experiencing, anger at themselves for not protecting Clair and a strong sense of pleasure in being her parents. They were able to give a rich and detailed picture of Clair, of her imagination; her sense of humor, which included making up funny words and enjoying making them laugh; her sense of drama and her capacity for play. They described her as having been confident and outgoing before the dog bite, but said she had become increasingly clingy and easily frightened. The parents described their sense of guilt for not heeding the warning signs that their dog was increasingly territorial, particularly following the birth of their now 6-month-old son. Clair had accepted their explanation without question that Rex went to live on a farm where he had more room to roam. They felt slightly conflicted about not telling her the full truth—that he had been euthanized due to the aggression—but they wished to protect her from any undue feelings of guilt should she associate the bite with his death. What was striking, against the backdrop of a longer history of working with vulnerable parents who had grave difficulty apprehending or considering their child’s unspoken worries, was that Clair’s parents could do so without prompting. It was also telling that both parents spoke freely and neither seemed to dominate. Emily was emotionally more intense than Mark, but they seemed to negotiate areas of differing perspectives, which were minimal, freely. I felt confident in their capacity to build an alliance with me on behalf of their daughter.

As we planned for Clair’s first visit to see me, I let the parents know that I suspected Clair had transformed her fear of her dog, the traumatic stress of the bite and his disappearance into a smaller, more manageable fear: spiders and ants. At her age, she was grappling both with the continued need for parental protection and support as well as the need to feel a sense of mastery and competence.2 Her symptoms of increased clinging, nightmares and a few toileting accidents also suggested some regression in the face of the anxiety about the sudden harm that befell her. I suggested that we use play as the medium to help her express her worries and they agreed. They did not need much convincing that young children often express their feelings, thoughts and wishes in play vs talk. Their capacity to understand their child’s developmental needs and to accept my guidance and support also marked something of a shift from working with families with less-than-secure attachment templates. These parents could be flexible in their understanding of their daughter and use me as a source of support.3 I helped them consider how they would introduce me to her and they liked the idea of telling her I was a person who would help her with her worries and fears.

In preparation for Clair’s first visit, I made sure the spider and bumble bee puppets were at the top of the puppet bin in my office. As she entered the office, she initially stayed close to her mom. I let her know my office was a place where children with worries came to play and talk, that she could “play or not play, talk or not talk.” The choice was hers. I had prepped Emily that we would let Clair take the lead in play, and that we would not provide directives or instructions. As they settled in, another clue to Emily’s capacity to support Clair would be if Emily could allow Clair to set the pace. She responded to Clair’s exploration and mirrored Clair’s interest in the toys. Though I had hoped that Clair would notice the puppets, I did nothing to draw her attention to them. Within minutes, the child who was afraid of spiders and ants found her way to the puppets and pulled them out. She squealed and tossed the spider to her mom, who asked Clair what she should do with the spider. Clair said, “Smash him!” Emily pretended to smash the spider into the ground. Over and over, Clair retrieved the puppet and re-enacted the same scene, as her tense anxiety began to dissolve into laughter. I commented how good it felt that her mom could take care of the scary spider. In that first session, Clair eventually explored the rest of the room and as the time came to end, she agreed she wanted to come play again.

In the second session, Clair went right to the puppet bin, put on the bee puppet and gave her mom the spider puppet. With a somewhat muted expression, Clair began to sting the spider puppet. In a stage whisper, I asked Clair what the spider puppet should be saying. “Owww, stop it!” Clair replied. As Emily followed Clair’s lead, Clair became increasingly animated. Intuitively, Emily comprehended what Clair was conveying and began to add emotion to her responses, saying, “Owww, that hurts! I don’t like that!” and “You are scary…go away!” I verbalized the pretend aspects of Emily’s responses so that Clair, who, at 3, could still confuse reality with fantasy, would not become overwhelmed. I was relieved to see Emily’s capacity to read Clair’s underlying emotions and to put her daughter’s experience into words, albeit displaced into play. Offering Clair a “mirror”4 of the fear and pain she experienced would allow her to know that her parents understood her experience and could help her make sense of it. Ultimately, this would help Clair digest and master the experience. Emily’s capacity to attune to Clair’s internal state bode well for her recovery. The ultimate aim was to reduce the feelings of helplessness and fear Clair was currently experiencing and to regain a sense of being safe and protected. What was also notable in these first two sessions was Clair’s ease in orienting to the room, not in an indiscriminate way, but in a relaxed, curious mode. Children with histories of more complex and relational trauma are often far more chaotic and unfocused in their play and exploration or inhibited and overly cautious and compliant. Another difference was the rapidity with which she was transforming her play, it was dynamic, not grim or stagnant.5

In the third session, Clair assigned me the spider puppet and began to sting me. In a stage whisper again, I asked Clair how the spider was supposed to feel about getting stung. She said, “Mad!” I found it interesting that as she moved into a more “negative” emotion, she drew me in to the play as opposed to her mother. I did not comment on it. As Clair kept stinging the spider, I worked to elaborate more of what I imagined her experience to have been. Even though her parents had quickly responded and taken Rex off of her, she had been bitten several times. How long it must have felt like the attack had lasted and how helpless and little she must have felt. I exaggerated my responses, and moved my body and hand trying to stay out of the bee’s way. I yelled, “Stop it, Bee! That hurts, I don’t like it!” and “No matter how much I yell or move, the bee won’t stop! I’m scared!” in various forms and words. Clair took enormous pleasure in being the powerful bee, beginning to master the littleness and helplessness she had felt. As we ended the session, I commented how good it must feel to be the powerful one and how she had helped me to understand how it felt to be little and scared.

In the next session, Clair had me adopt the spider puppet again. Wanting to weave in the theme of safety and protection, I said aloud as I was being “attacked,” “Help, somebody help me!!” with a glance and a nod toward Emily, who quickly picked up on my cue and came to my rescue, telling the bee to go away and putting her hand between the bee and the spider. Shortly after, Clair changed the game. She took the spider away from me and gave me the bee. I asked what my role was, and she told me I was supposed to chase and sting the spider. I told her I would pretend to be the scary bee, again reinforcing the fantasy vs reality aspect of our play. As the bee began to sting the spider, she ran behind her mother, who forcefully pushed my bee away saying, “You stay away from my spider! I won’t let you hurt her!” Clair giggled and came out from behind her mother to start the game again. Over and over, she declared through her play her need for her mother’s protection, and over and over again, her mother asserted her desire and capacity to protect Clair. They were working collaboratively to repair the rupture of the “protective shield” of safety that Rex had torn.6

That style of play continued into the next two sessions, but increasingly, Clair became interested in other aspects of the playroom. She “cooked” and fed us from the kitchen area, she tucked a baby doll into the cradle, humming it to sleep. She seemed to be reminding herself of the layers of nurturing and protection she had experienced in the past and could access now. Emily reported that Clair’s clinging and fears had diminished and that she seemed to be the confident child she had been. In one session, with her father, she asked directly where he was when “Rex bited me.” He apologized directly to her and said he would work very hard to make sure she stayed safe. She paused briefly, looking at him solemnly, as if contemplating his words, then smiled slightly and offered him a cookie.

In our last session, Clair played freely, only briefly referencing the bee and spider. She eventually settled on carefully constructing a tall house from the cardboard “bricks” in the office. Once the house was stable and sturdy, she carefully selected a number of animals and figures, surrounding the house with them. Counting in the fanciful way of 3 year olds, she announced proudly that the house had “19 protectors!” We affirmed that it was indeed a very safe, strong house.

Infants and young children who experience a trauma within the backdrop of a secure relationship may still suffer the posttraumatic stress symptoms, but their recovery is thought to be more readily accomplished. This was true of Clair. In eight sessions, she recaptured the sense of safety and protection that had shielded her in the past. The security of the relationship with her parents allowed her to experience and express her distress, not needing to defend against it too fiercely, because she “knew” her parents had comprehended and accepted her range of feelings in the past. Their sensitive response to her distress, their willingness and capacity to seek help and the ability to let her tell her story of the feelings associated with the attack all allowed for a rapid recovery. Their capacity to meet her needs in the present, and her ability to accept their efforts at soothing her and repairing the disruption to her sense of safety, was girded by a relational history of security.

References

- Fraiberg S, Adelson E, Shapiro V. Ghosts in the nursery: A psychoanalytic approach to the problems of impaired infant-mother relationships. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1975:14:387-421.

- Davies D. Child Development. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011.

- Wallin DJ. Attachment in Psychotherapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007.

- Gergely G, Watson J. The social biofeedback model of parental affect-mirroring. International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 1996;77:1181-1212.

- Gil E. Helping Abused and Traumatized Children: Integrating Directive and Nondirective Approaches. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006.

- Lieberman AF, Padrón E, Van Horn P, Harris WW. Angels in the nursery: the intergenerational transmission of benevolent parental influences. Infant Mental Health Journal, 2005;26:504-520.