Infant mental health specialists recognize the unique strengths and needs of each family. An understanding of variations in child temperament can help clinicians provide developmental information that is specific to each baby. It can also be used to help parents recognize and foster their children’s individual potential. Research confirms that individuals vary in their degree of sensitivity to environmental influence including being more or less impacted by parenting behaviors. Increased sensitivity may be a disadvantage in an unfavorable environment, but it also allows a child to take full advantage of a positive and supportive environment (Belsky & Pluess, 2009). What is generally referred to as a “difficult” temperament has been shown to be associated with this type of increased sensitivity to parenting (Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van Ijzendoorn, 2007).

At the same time, children with difficult temperaments may present the most challenges to receiving an optimal level of care. A difficult temperament is characterized by heightened reactivity and emotionality. Children may react easily and intensely and are often described as easily upset. Research has shown mixed results in terms of the effect a child’s temperament has on parenting. This is particularly important when it comes to so-called “difficult” or challenging temperaments. Some research indicates that children with more reactive temperaments are more taxing for parents and are more likely to receive harsher or less responsive care (Clark, Kochanska, & Ready, 2000; Jaffee et al., 2004). Still, other studies show this same temperament elicits greater responsiveness and maternal involvement (Kochanska, Friesenborg, Lange, & Martel, 2004; Pettit & Bates, 1984; Sroufe, 1985). This study examines how children’s temperamental predispositions evoke particular responses from parents and the manner in which parental qualities affect their responses to children’s temperament.

Research Questions

First, we were interested in identifying naturally occurring patterns of child temperament and parental response to that temperament. We expected to see that some parents experience pronounced distress in relation to heightened child negative emotionality while others do not. Second, we examined the relationships between the patterns and parenting quality over time. We hypothesized that highly emotional children may be more likely to experience negative parenting behaviors from highly distressed parents than their less reactive counterparts or from parents who were more satisfied with the parent-child relationship. As a next step, we examined whether additional parent and child characteristics or behaviors distinguished among patterns that included children high in negative emotionality. The aim was to determine factors that distinguish between parents of children high on negative emotionality experiencing higher levels of distress and dissatisfaction in the parenting role from those who do not in order to inform future interventions for so-called “difficult” children.

Overview of Study Methods

The sample included 2,329 Early Head Start eligible children (1,184 males) and their primary caregivers from the National Early Head Start Research and Evaluation (EHSRE) Project (Love et al., 2005).

At enrollment, caregivers were a mean age of 22.6 (SD = 5.77) years and children were a mean age of 15.02 (SD = 1.48) months. Caregivers were 37% White, 34% African American, and 23% Hispanic/Latino, most with no more than a high school education (74.4%). Annual gross income averaged $9,277 (SD = $8,421).

We measured temperament by parent report using the Emotionality Activity Sociability and Impulsivity (EASI) measure (Buss & Plomin, 1984) at 14 months. Parental distress and parent-child dysfunctional interaction (dissatisfaction with the parent-child relationship) were assessed via parent report using the Parenting Stress Index (Abidin, 1995). Parental Distress refers to distress related to the parenting role and the Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction addresses the parent’s dissatisfaction with the parent-child relationship. Some of the questions have to do with whether the child’s behavior is what the parent expected.

To answer the second research question regarding how parent/child patterns are related to parent behaviors, we looked at parental negative regard toward the child during play using a measure called the “3-bag task”. The 3-bag assessment is a videotaped parent-child semi-structured play task that is then coded by an observer. Parental negative regard included things like expression of anger toward the child or disapproval or rejection of the child. We used ratings of parents collected when children were 24 and 36 months old, and when children were five years old.

Results

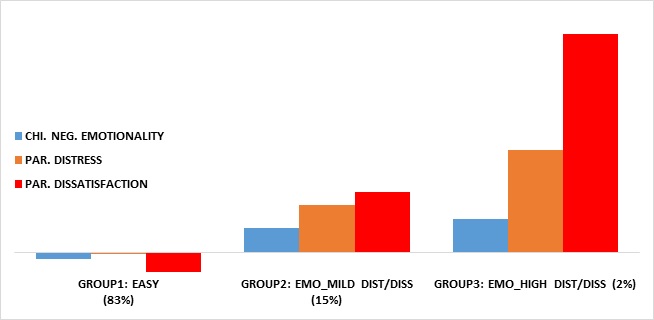

Patterns of Child Temperament and Parental Response. Consistent with our hypotheses, analyses (Figure 1) revealed variations in patterns of child temperament and parenting distress and/or dissatisfaction.

Figure 1. Patterns of Child Emotionality and Parental Distress/Dissatisfaction

The first group represents what we would think of as “easy” children. They were low on negative emotionality, and their parents experienced very little parenting distress and little dissatisfaction in the parenting role. This is the largest group and contains 83% of the parent-child dyads. The second and third groups were both high on negative emotionality (the “difficult” children), but what distinguishes the third group is the magnitude of the distress and dissatisfaction in the parent that goes with it.

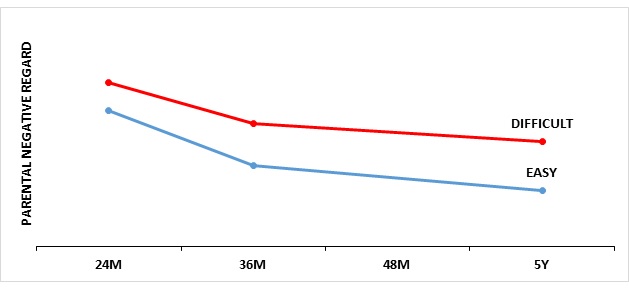

Parental Negative Regard. For the entire sample taken as a whole, parental negative regard exhibited toward the child in the free play episodes decreases over time from child age 24 months to 5 years. The first set of comparisons evaluated possible group differences in change in parental negative regard between the first group, comprised of temperamentally “easy” children and their parents, and the two remaining groups, comprised of highly emotional children and their parents, together. As seen in Figure 2, children in the groups characterized by heightened emotionality tend to experience significantly higher levels of negative regard at 24 months (1.43) than those with a less reactive disposition (1.52) as well as a significantly slower rate of decrease Δχ2(3, N = 2022) = 28.71, p < .001, over time.

Figure 2. Group 1 compared to Groups 2 and 3 Combined

Those in the “difficult” groups experience more parental negative regard to begin with and that negative regard decreases less by the time children are 5 years old. That is, parents were more negative toward their emotionally reactive children at the first assessment and continued to be more negative over time as compared to parents whose children had a less challenging temperament.

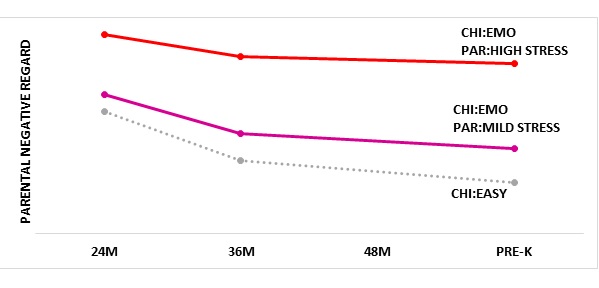

The second set of comparisons evaluated possible differences between the two groups that included children with heightened emotionality. This was done to compare highly emotional children with distressed parents to those whose parents did not experience such distress. As seen in Figure 3, highly distressed parents exhibit significantly higher levels of negative regard (1.70) toward their highly emotional children than parents of similar children who are less distressed and more satisfied in the parenting role (1.49). Results also show significant difference between groups, Δχ2(3, N= 331) = 13.91, p = .003, in the rate of decline in parental negative regard over the study period.

Figure 3. Group 2 compared to Group 3

For parents of highly emotional children, those who are highly distressed show much more negativity toward their children at the first assessment than less distressed parents of equally emotional children. These highly distressed parents show very little, if any, lessening of that negativity over time.

Group Differences on Additional Characteristics. Parents in the highly distressed group tended to perceive more behavior problems, F(2,1348) = 68.20, p < .001, in their children despite no significant differences between groups 2 and 3 on observer rated behavior scales. Parents who are better able to accept and interact with their child’s temperament are characterized by greater knowledge of infant development, F(2,1348) = 24.86, p < .001.

Conclusions

Results highlight the importance of parental perception in shaping the emerging parent-child relationship. Parenting behaviors were not impacted by a challenging child temperament, but rather by the parents’ acceptance and response to that temperament. Parents who experienced substantial distress and who saw their relationship with their child as less satisfying exhibited more and longer lasting negative regard toward their children. However, highly emotional children whose parents did not experience such distress and had more positive perceptions of the relationship showed levels of negative regard similar to parents of “easy” children. A notable difference in these more accepting parents of highly emotional children is that they had greater knowledge of child development.

Key Implications for Practice

- Offering developmental guidance in terms of variations in temperament and reactivity could help parents form accurate expectations and improve their understanding of their unique child’s behavior. This could be especially helpful for parents of children with challenging temperaments.

- IMH specialists could offer interaction guidance regarding effective strategies parents could use to model and facilitate self-regulation in their highly emotional children. This could improve parental self-efficacy. At the same time, it could assist these children in successfully managing their tendency toward increased reactivity and emotional response. Strengthening the parent-child relationship can be particularly advantageous for children who are more sensitive to environmental influence.

References

Abidin, R. R. (1995). Parenting stress index, third edition: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Belsky, J., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2007). For better and for worse: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 300–304. http://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org.proxy2.cl.msu.edu.proxy1.cl.msu.edu/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00525.x

Belsky, J., & Pluess, M. (2009). Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin, 135(6), 885–908.

http://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org.proxy2.cl.msu.edu.proxy1.cl.msu.edu/10.1037/a0017376

Buss, A. H., & Plomin, R. (1984). Temperament: early developing personality traits. Hillsdale, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Clark, A. L., Kochanska, G., & Ready, R. (2000). Mothers’ personality and its interaction with child temperament as predictors of parenting behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(2), 274–285.

Jaffee, S. R., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Polo-Tomas, M., Price, T. S., & Taylor, A. (2004). The Limits of Child Effects: Evidence for Genetically Mediated Child Effects on Corporal Punishment but Not on Physical Maltreatment. Developmental Psychology, 40(6), 1047–1058

http://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org.proxy1.cl.msu.edu/10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1047

Kochanska, G., Friesenborg, A. E., Lange, L. A., & Martel, M. M. (2004). Parents’ Personality and Infants’ Temperament as Contributors to Their Emerging Relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(5), 744–759.

http://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org.proxy1.cl.msu.edu/10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.744

Love, J. M., Ross, C., Raikes, H., Constantine, J., Boller, K., Brooks-Gunn, J., … Vogel, C. (2005). The Effectiveness of Early Head Start for 3-Year-Old Children and Their Parents: Lessons for Policy and Programs. Developmental Psychology, 41(6), 885–901.

Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (1984). Continuity of Individual Differences in the Mother-Infant Relationship from Six to Thirteen Months. Child Development, 55(3), 729–739.

http://doi.org/10.2307/1130125

Sroufe, L. A. (1985). Attachment Classification from the Perspective of Infant-Caregiver Relationships and Infant Temperament. Child Development, 56(1), 1–14.

http://doi.org/10.2307/1130168

Contact Information

For more information contact: Danielle Dalimonte-Merckling at dalimon5@msu.edu.