In this research brief we will present research that explores family factors predicting parents’ negative responses to toddlers’ emotions. It is important to learn more about mothers’ and fathers’ negative response as we understand that these responses impact the way that children are socialized to understand and express emotion. Parental emotion socialization practices are thought to be a function of parenting and family processes embedded in the family context1. We examined (1) parents’ beliefs about when and to what extent children should express emotions2, (2) parents’ handling of their own emotions1,3,4, and (3) the co-parenting relationship5— each of which reflect key processes in the family context that likely influence parents’ socialization practices, particularly how parents respond to toddlers’ expressions of emotions such as anger, fear, and sadness. As defined by Gottman2, parental beliefs about emotion can include dismissing attitudes such that children’s expressions of strong emotions such as anger, sadness or fear are met with anger, sarcasm or shaming. Generally, these types of reactions to children’s emotions are thought to be detrimental to children’s emotional development while more supportive responses are considered more optimal. Parents’ skills in regulating their own emotions, particularly in front of children, are also powerful emotion socialization agents. Imagine a parent who models dysregulated anger, such as screaming in anger rather than modeling how to more constructively express anger. Parents who have difficulties managing their own powerful feelings are more likely to respond to their children’s expressions of emotions in a negative fashion4. Likewise, the co-parenting relationship can be characterized by hostility and anger that spills over into parenting behaviors6,7. Triangulation, for example, occurs when one parents pulls the child into parental conflict by forcing the child into an alliance against the other parent. Examples of triangulation include things like one parent saying negative things about the other parent to the child and degrading the other parent. Triangulation is very harmful for the child because it places the child in the impossible circumstance of having to negotiate and deal with conflict between the parents8. The ways that parents raise the child together is called the co-parenting relationship. The co-parenting relationship is sometime characterized by very negative processes such as triangulation.

Research Questions

We were interested in how these three socialization contexts– parents’ emotion dismissing beliefs, parents’ dysregulatory problems, and co-parenting—were independently and in interaction related to mothers’ and fathers’ responses to toddlers’ expressions of anger, fear and sadness.

Methods

Participants included 83 couples (Mage mothers = 31.96 years, SD = 4.62; Mage fathers = 33.88 years, SD = 5.25) with toddlers (Mage = 29.06 months, SD = 4.40), reflecting a primarily Caucasian, middle class sample. Mothers and fathers separately completed measures of co-parenting behaviors (Co-parenting Questionnaire9, triangulation subscale), difficulties in parents’ emotion regulation (Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale10), parents’ emotion dismissing beliefs (Emotion-Related Parenting Styles Questionnaire11), and parents’ self-reported responses to toddlers’ expressions of anger, sadness and fear represented in a series of vignettes (Coping with Toddlers’ Negative Emotion Scale12).

Results

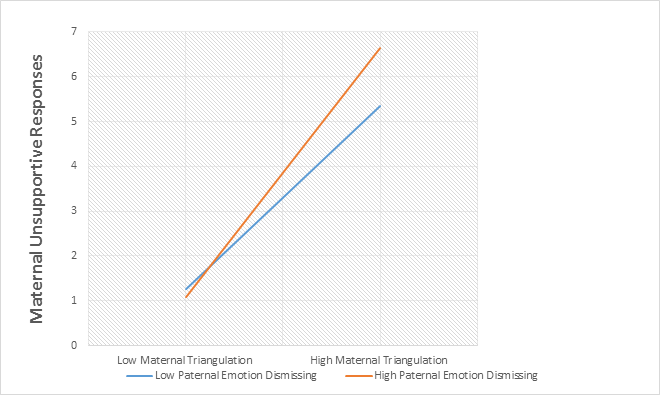

Parental age and income were not significantly related to the outcomes and were dropped from further analyses. Child age and gender were not significantly related to parental responses to toddlers’ emotions but were retained for conceptual integrity. Both mothers’ and fathers’ own emotion regulation difficulty were not significantly related to parental responses to toddlers’ emotions. We were surprised at this result. Most parents, though, rated themselves as being very high in emotion regulation skills (and self-reports may not reflect what is actually happening or what the parents’ emotion regulation skills really are). For fathers, perceptions of triangulation and emotion dismissing beliefs were related to their unsupportive responses to toddler emotions. This model explained about 25% of the variances in fathers’ unsupportive reactions to toddlers’ anger, fear and sadness. Similarly, for mothers, triangulation in the co-parenting relationship and emotion dismissing beliefs related to their unsupportive responses to toddlers’ emotion. However, for mothers only, the interaction between maternal perceptions of triangulation and paternal emotion dismissing beliefs was significantly related to mothers’ unsupportive responses, explaining about 30% of the variance in mothers’ negative responses to toddlers’ anger, sadness and fear. As illustrated in the figure below, when mothers reported a conflictual co-parenting relationship (characterized by triangulation) and when fathers had strong emotion dismissing beliefs, mothers responded more negatively to toddlers emotions.

Figure 1. Paternal emotion dismissing beliefs moderate relations between mothers’ perceived triangulation in the co-parenting relationship and their unsupportive responses to toddlers’ negative emotions. Mothers use more unsupportive responses when they perceive triangulation in the co-parenting relationship and when fathers’ have emotion dismissing beliefs.

Discussion

For both mothers and fathers, their own emotion dismissing beliefs and their perceptions of triangulation (such as the other parent was using their child as a pawn or ally in response to a conflictual parenting relationship) were related to unsupportive responses to toddlers’ emotions. Collectively, this suggests that multiple dimensions of the emotional climate in the home are related to parents’ early emotion socialization behaviors. In our study, negative climate in the home clearly related to parents’ harsh responses to toddlers’ strong emotions. Interestingly, mothers were influenced by fathers’ dismissing beliefs in interaction with their perceptions of triangulation in the co-parenting relationship. This is somewhat surprising because some of our prior work suggests that fathers tend to be more heavily impacted by mothers’ behaviors than mothers are by fathers13. It may be that in the earliest years of parenting mothers are particularly sensitive to the dynamics in the parenting relationship. Towards the end of toddlerhood, parenting tends to fall into relatively stable patterns. Prior to that point, however, parenting behaviors may be more vulnerable to the evolving dynamics as a couple transitions to parenthood. In summary, results underscore the strong influence of the co-parenting relationship and beliefs about emotions for both mothers and fathers, but also highlight the ways in which complex interactions differentially influence the socialization practices of mothers and fathers. Home visitors can play an important role in educating parents about findings like this and helping parents navigate the early family environment.14

Key Points:

- Emotion socialization in the home reflects multiple contexts including parents’ own beliefs and behaviors, and the emotional climate of the co-parenting relationships.

- Supporting parents in exploring their own beliefs about emotions and the expression of emotions may play a key role in helping parents develop supportive responses to toddlers’ strong emotions.

- Home visitors can support positive emotion socialization by promoting emotional strengths in the parenting and the co-parenting relationship. Supporting parenting partners in developing positive tools to manage the co-parenting relationship has benefits for toddlers’ early emotional development.

References

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social development. 2007;16(2):361-388.

- Gottman JM, Katz LF, Hooven C. Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: Theoretical models and preliminary data. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10(3):243.

- Martini TS, Root CA, Jenkins JM. Low and middle income mothers’ regulation of negative emotion: Effects of children’s temperament and situational emotional responses. Social Development. 2004;13(4):515-530.

- Carrère S, Bowie BH. Like parent, like child: Parent and child emotion dysregulation. Archives of psychiatric nursing. 2012;26(3):e23-e30.

- Pape Cowan C, Cowan PA. Two central roles for couple relationships: Breaking negative intergenerational patterns and enhancing children’s adaptation. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2005;20(3):275-288.

- Stroud CB, Durbin CE, Wilson S, Mendelsohn KA. Spillover to triadic and dyadic systems in families with young children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25(6):919.

- Margolin G, Gordis EB, John RS. Coparenting: a link between marital conflict and parenting in two-parent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15(1):3.

- Feinberg ME. The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2003;3(2):95-131.

- Margolin G. Coparenting Questionnaire. Unpublished instrument, University of Southern California, Los Angeles. 1992.

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26(1):41-54.

- Paterson AD, Babb KA, Camodeca A, et al. Emotion-Related Parenting Styles (ERPS): A short form for measuring parental meta-emotion philosophy. Early Education & Development. 2012;23(4):583-602.

- Spinrad T, Eisenberg N, Kupfer A, Gaertner B, Michalik N. The coping with negative emotions scale. Paper presented at: International Conference for Infant Studies2004.

- Cho S, Brophy-Herb, H., & Vallotton, C. Actor and partner effects in the relationship between maternal and paternal parenting behaviors in toddlerhoodunder review.

- Kolak AM, Volling BL. Parental Expressiveness as a Moderator of Coparenting and Marital Relationship Quality*. Family Relations. 2007;56(5):467-478.