When a child has a secure attachment, he or she can explore the surrounding world safely, trusting and knowing that their parent or primary caregiver will welcome him or her back with open arms. When she lived with her mother and father, Eva’s parents were her primary attachment figures whom she would turn to in times of distress for comfort and safety. However, Eva experienced and witnessed abuse and neglect at the hands of her parents until she was removed from her home at 27 months of age. Eva was caught in a terrorizing bind between the drive to seek safety from her mother and father, who at times were the root cause of the distress and unpredictable fear or harm she was experiencing. When a child must constantly live in this bind, searching for a way out and living in an unsolvable state of fear, disorganized attachment emerges.

Both of Eva’s parents struggled with drug abuse, mental health concerns, poverty and their own trauma histories. These and many other factors put Eva and her older siblings at risk for abuse and neglect, as well as the development of disorganized attachment. After their home caught fire, Child Protective Services (CPS) was called. There had already been several other calls and a pending investigation, so CPS wanted to remove the children. However, the mother was willing to sign over guardianship to an aunt and uncle so the children did not have to go into foster care. She was also willing to go into an inpatient drug rehabilitation facility. The mother was also pregnant. CPS was not going to allow the new baby to go home with the parents; therefore, the aunt and uncle agreed to take the baby when mom gave birth. Eva and her siblings went to live with her aunt, uncle and their children, making a grand total of eight children under one roof. The aunt sought out services for the children shortly after their arrival. Due to Eva’s age, she was referred to infant mental health services. But this is only one part of Eva’s story. I want to tell you a little about where she was, but also about how far she has come.

What About the Baby? Where’s Eva?

I will never forget my first visit with this family. This was only my second or third case as a new clinician. I was eager and anxious for the opportunity to apply all that I had learned in school to the real experience of being with families. I remember walking up to the house on a crisp autumn day, leaves crunching at my feet and paperwork in hand. Gail, Eva’s aunt, greeted me at the door. She was a short woman, in her early 40s, wearing blue jeans and a grey hooded sweatshirt. She brought me to the kitchen table that looked as though it had been cleaned and well prepared as the place that we were to meet. I simply asked Gail to tell me a little more about Eva and what brought her to treatment at this time. As I listened to the story, I remained attuned to and curious about the matter-of-fact way in which she walked me through her experience of Eva and her behaviors.

I will never forget my first visit with this family. This was only my second or third case as a new clinician. I was eager and anxious for the opportunity to apply all that I had learned in school to the real experience of being with families. I remember walking up to the house on a crisp autumn day, leaves crunching at my feet and paperwork in hand. Gail, Eva’s aunt, greeted me at the door. She was a short woman, in her early 40s, wearing blue jeans and a grey hooded sweatshirt. She brought me to the kitchen table that looked as though it had been cleaned and well prepared as the place that we were to meet. I simply asked Gail to tell me a little more about Eva and what brought her to treatment at this time. As I listened to the story, I remained attuned to and curious about the matter-of-fact way in which she walked me through her experience of Eva and her behaviors.

While working to remain present to the unfolding story, I noticed a question fighting for my attention, like a toddler tugging on my shirt needing me to see what he was seeing that instant. The literal question I had heard so many times before in the classroom kept popping into my head, “What about the baby? Where’s Eva?” For a new infant mental health clinician, mustering up the courage to ask a question—even one as obvious as this—can leave us wanting to run for the door. I waited, not only to take a moment to turn down my inner critic for not wondering this sooner, but for an opportune time to wonder out loud, “Where is Eva?” with genuine curiosity. Gail looked at me and then pointed underneath the table. I remember the high-pitched sound the chairs made against the hardwood floors as we pushed them out from the table in unison, still locking eyes with one another. It felt like an unspoken agreement between the two of us that neither would move first, that we would look together. I wonder, reflecting on this moment now, if we also silently and mutually agreed that from now on were going to be in this together.

Eva, now 30 months old, was lying on her side at Gail’s feet under the table curled up in the fetal position. Her limbs were tightly tucked and woven into one another, covering her head, which was folded into her chest. Gail and I came back together above the table. I asked what seemed to work to pull Eva out of this? What did not work? Gail said that Eva could not tolerate physical touch, especially when upset. She had tried holding her, but she said Eva “just isn’t interested in that.” Gail said that she allowed her to sit there, because she was afraid to do anything that might cause Eva to go into one of her temper tantrums. I asked if she could describe to me what those temper tantrums looked like. She described how Eva would hurt herself and others. She bit, hit, kicked and threw herself onto the floor.

I asked what she thought Eva needed when she was so upset, and Gail responded, “I don’t know…. Help. Someone there.” I reflected that Gail understood what Eva needed and tried to soothe her by picking her up, but that Eva acted as if she “just isn’t interested in that.” We explored ways Gail might be able to soothe Eva and let her know she was there without physical touch. I then asked if we could try one of her ideas in that moment.

We both moved from our chairs to the floor to test our hypothesis. I sat near Gail and Gail sat close to Eva. I gently spoke first as the narrator, telling Eva that Gail was right there and that she would be there when she was ready. We sat together in silence for quite some time until Gail finally spoke. She said only two words, but two words that truly resonate with a child like Eva. Two words that would symbolize our work, and that we would continue to carry with us throughout our time together. Gail quietly said, “I’m here.”

Some time passed after Gail spoke, and Eva slowly began to unfold and untuck herself limb by limb until, eventually, she peeked her head up. She stared at us with her bright blue eyes; her brown curls all swept up in a messy ponytail high atop her head. We sat there together, with Eva and Gail not moving. Stillness filled the air like a thick fog. The calm did not last long, and soon Eva was off into the kitchen. She got onto the counter and opened cabinets, grabbing at anything she could reach. Plastic cups, bowls and plates crashed to the floor around her. Then, Eva was on her tiptoes with her fingertips barely grazing a bag of chips that sat atop the refrigerator. She moved her hand continuously in a sweeping motion until she knocked the entire bag onto the floor, chips flying everywhere. This all happened in a matter of seconds. Gail ran to her and grabbed her off the counter. Gail and Eva quickly fell into the dance that Gail had earlier described to me, but now I was seeing the live version. When Gail firmly told Eva “no,” Eva froze like a statue. She threw herself backward onto the hardwood floor and banged her head so hard that just the thought of the thud still makes me shudder. She began to scream and tossed her body around on the floor while biting at her hands and arms, ripping at her flesh. She reached for her ponytail and began to frantically pull at her hair, removing pieces by the handful. Gail ran over to her and gently restrained her. I watched as pain and panic washed over Gail’s face like a tidal wave, leaving a blank stare as she held this screaming, flailing child. I left their home that day wondering, “How am I going to do this? This isn’t what I expected! How can I help this child and this family?” Were those some of the very thoughts and questions Gail had asked herself?

Light Peeking out from the Darkness

About a month and a half into our work together, in addition to developing Eva’s sense of safety, we had also begun to think about ways to help Gail become more attuned to Eva’s needs. This was important because we had identified that Eva, who had very little language, might not communicate, cue or signal her needs as clearly as other young children. I watched and wondered week after week as Eva and Gail showed me how they related to one another. The intensity and frequency of Eva’s behaviors were unlike any I had ever seen in a child before. Over time, a pattern that felt ritualistic in nature became apparent.

When Eva became distressed—though the triggers were never predictable—she would run “to” and sometimes “at” Gail. Gail anticipated Eva’s arrival with learned hypervigilance, bracing herself, eyes open wide and locked onto her every movement. Eva arrived like a freight train but slammed on the brakes the moment she reached Gail. Going toward comfort and then freezing is a hallmark example of an incoherent strategy in a child with a disorganized attachment relationship. Although Eva momentarily sought out her aunt, she was afraid of being hurt based on many experiences with her biological parents. Anticipating anger and abuse, she faced a dilemma of both wanting and being afraid of her parents. By 27 months of age, this belief was well-solidified as her working model and continued in her relationship with her aunt.

Eva would be momentarily frozen in time as Gail anxiously scrambled to restrain her in anticipation of what was to come. Eva would then begin to scream and hit Gail, trying to bite at Gail’s arms and hands. Eva thrashed around as Gail held her in hopes that she could keep Eva from hurting either one of them further. Eventually, Eva would shimmy herself to the ground and break free from Gail’s grip. Eva then alternated between biting her hands and arms and ripping at her hair. She would throw herself onto the floor, slam her head on the ground and repeatedly bang her head. Gail would try to restrain Eva, and the cycle would begin again. At times, Eva would run from Gail into the bathroom, lie in the fetal position in the dark and cry alone. Gail expressed feelings of confusion and frustration; she felt that Eva seemed to calm down better when left alone. When she tried anything, it “made things worse,” and she just felt exhausted.

Although this had become an all-too-familiar scene that happened multiple times within our two-hour visits, one day something shifted. Eva was coloring at the table and dropped the box of crayons onto the floor. She became very distressed and initially looked to Gail and started to walk toward her. Then she froze, threw herself onto the ground and started screaming, pulling her hair and biting herself. Gail started to go to her, but before she could get there, Eva ran into the bathroom and lay on the floor in the fetal position, limbs tightly bound. Gail and I sat together in the moment. She broke the silence by anxiously saying something about Eva just needing to be in there. She said that she would come out when she was ready. She indicated that Eva did not want her and that, if she went in, it would just upset Eva further.

I reflected about what had happened right after the box of crayons fell onto the floor. I wondered if Gail had noticed what Eva did first. Gail described the scene as Eva falling onto the floor and having a temper tantrum. I then described what I had seen Eva do first. She had looked to Gail and started walking toward her. I wanted to be careful of implying that Eva “wants you” or “needs you,” because this was early in our work and it might have been too much for Gail. I worried that my words might sound judgmental or ignite her inner critic for not noticing this herself. Gail laughed a little and said, “See! How can I ever know what she wants?” I empathized with how confusing and frustrating it must be when a child’s actions seem like they are pushing us away, but we know that they really need us. I wondered if, in this moment, Eva’s behavior was showing us one thing, while she really needed something else. Gail and I decided to move together and sit outside of the bathroom where Eva lay in the dark, alone.

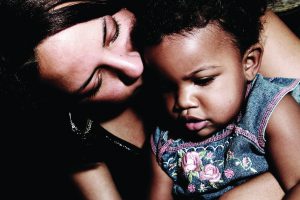

As we sat together, I thought out loud back to our first visit and wondered if Gail remembered the two words she had said to Eva underneath the table that day. Gail initially looked at me, puzzled, but I watched a shift happen, as if someone flipped a switch, and the words were suddenly there. “I’m here,” she said with a grin. She then turned towards the dark bathroom where Eva lay and said, “We are here, Eva, when you’re ready.” We sat outside of the bathroom for a long time before Eva moved. Her first movement was small. She slowly peeked out with one eye barely moving, just to make sure we were indeed still there. Gail and I looked at one another and smiled. Shortly after, Eva got up and moved over to Gail, placing her head on Gail’s lap. I wondered if a gentle hand on Eva’s back might feel ok to Gail and Eva. Gail gently placed her hand on Eva’s back and then quickly asked if we could all clean up the crayons together. Gail then placed her hands behind her, arching her back slightly and creating space between her and Eva, making me wonder what physical closeness meant to her as well.

Thinking back to our first visit when she described Eva as “just not being interested in that,” I wondered if she was really telling me something about herself. I kept this on a shelf in my mind and brought it forward later in our work together when Gail opened up about not being a “touchy-feely” person. Gail opened a tiny window that day for me to begin to see her internal working model and to understand what she brought to the relationship. Learning more about Gail, I wondered about the challenges this dyad faced: a child who needed help to feel safe and secure and to accept comfort in times of distress, but who might not always be able to seek it; and a caregiver who struggled with being needed and being close.

Eva shook her head yes in agreement to working together to pick up the crayons. She walked over to the table and picked up the crayon box. Gail and I picked up the crayons one by one placing them into the box that Eva held. Eva delighted in her responsibility of holding the box, and she gleamed with pride. I put words to this with a simple observation, and Gail was able to add, “Eva, thanks for holding the box.” After we finished, the two of them smiled at one another. Eva then walked over to Gail and gently pulled on her hand, bringing her to the kitchen to show Gail that she wanted something to drink.

There is a window behind the shower in the bathroom in Gail’s home. That day, the shower curtain was closed almost all the way, allowing just a sliver of light from the sun to pass through. I remember the ray of light touching the top of Eva’s head and shining onto Gail’s body, connecting the two of them in some way in that moment. But this was not the only thing connecting the two of them. It would be several months later when Gail began to share her own history with me; telling me stories of a similar childhood. I realize now I was sitting with two children that day, afraid and alone in the dark, telling each one of them in my own way, “I’m here.”

Hope for the Future

I have been working with this family for over four years now, and our time together is coming to an end as Eva ages out of our program. When working with a child with disorganized attachment, it is easy to feel lost or hopeless, just as they might feel. Although Eva was removed from her parents where the abuse and neglect had occurred, this new dyad has had its own challenges and triumphs. Establishing a trusting working relationship was a slow process. As we sat outside of the bathroom door week after week, following Eva’s lead and letting her know Gail was there, a parallel process was occurring as I was showing up week after week letting Gail know I was there. This child (and seven other children) need so much from a caregiver who struggled herself with being too close or needed.

Today Eva, now 6.5 years old, is no longer engaging in self-harming behaviors. She does not have extreme temper tantrums and is doing fairly well in her second year of school, with only occasional regressions. She frequently seeks Gail out for comfort in times of distress. Gail is working to be consistently available to her and is exploring what makes it difficult at times for her to do so. The greatest challenge and growing experience for me as a clinician was being patient as I worked with this family, not judging them and using their dance to guide my work. Through the process, I have experienced so much growth as a clinician, and I will continue to use what I have learned from my work with this family. Although there is darkness in the past experiences of this child and this caregiver, the light of hope for their future shines bright.