In the 10 years I’ve been an Infant Mental Health clinician, picky eating habits in children top the list of things families come looking for support in. “My kid only eats mac and cheese” or “He won’t eat a vegetable” are common phrases heard at an initial intake appointment. I’ve often wondered: What is picky eating? Is it behavioral/emotional, relational, medical, sensory or environmental? The answer I’ve discovered upon working with an Occupational Therapist (OT) for the past five years: All of the above.

In the 10 years I’ve been an Infant Mental Health clinician, picky eating habits in children top the list of things families come looking for support in. “My kid only eats mac and cheese” or “He won’t eat a vegetable” are common phrases heard at an initial intake appointment. I’ve often wondered: What is picky eating? Is it behavioral/emotional, relational, medical, sensory or environmental? The answer I’ve discovered upon working with an Occupational Therapist (OT) for the past five years: All of the above.

Research has shown that children with feeding challenges generally have more difficult temperaments, which leads to relationship conflicts and a lack of maternal confidence and competence in addressing these difficulties (Aviram et al., 2015). Through infant mental health services, a clinician can support children and families through navigating these difficult interactions, which can also address the children’s feeding challenges. However, psychological support is just one of the many important pieces that goes into addressing this complex issue.

In the field of mental health, we are well aware of the ‘anger iceberg,’ the idea that anger is an emotion that tends to be easy to see — the tip of the iceberg — but with many other emotions and experiences hidden below the surface. The field of occupational therapy has a similar metaphor around feeding.

For feeding therapy to be effective, the OT needs to take into consideration three overarching areas: the 1) psychological experiences with eating, 2) previous experiences with food/eating, and relationships with people around eating, and 3) oral motor skills and abilities to manage foods. One or a combination of these can be the reason the child is having difficulties. Due to the complexity of feeding, a team approach is required to have the highest level of success for overcoming challenges.

As Infant Mental Health clinicians, it is important to understand when it is problem feeding, not just picky eating.

As part of developmental guidance, and to be generally supportive, we may normalize picky eating, but we must also do our due diligence to help families discern when picky eating rounds the corner into problem feeding and when to refer to appropriate specialists.

So when would it be considered problem eating? It is not uncommon for toddlers to display preferences for specific foods or refuse to try new things that are introduced. By the age of three, children should have consumed at least 20 foods, with two to three items in each food group, on a consistent basis. Below are red flags for problem feeding; it is recommended that a child be referred to an OT, or other appropriate specialists, if at least two are present.

- Restricted diet with little variety

- Cries and falls apart when presented with new foods; complete refusal

- Refuses entire categories of food textures or nutritional food groups

- Almost always eats different foods at a meal than rest of the family; often doesn’t eat with the family

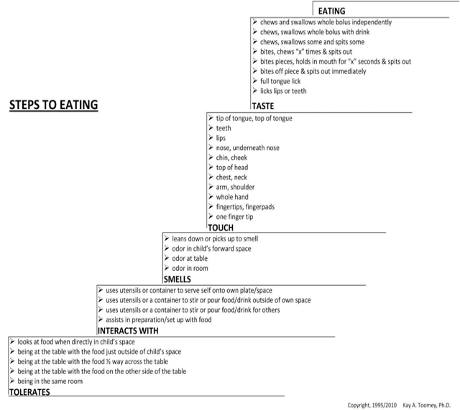

- More than 25 steps of the 32 on the Steps to Eating Hierarchy**

- Consistently reported by a parent as “picky eater” across multiple well child checkups.

- Significant loss of previously eaten foods (as some loss can be considered typical)

- Signs of aspiration: wet sounding voice after and during eating, sweating, sneezing, coughing, excessive amounts of saliva, etc. If any of these are present, seek medical assistance from a physician.

If a child is exhibiting any of the above, as well as the signs/symptoms below, a referral to a speech-language pathologist or medical specialist is likely needed.

- Ongoing poor weight gain

- Ongoing choking, gagging, or coughing during meals

- Problems with vomiting

- History of traumatic choking incident

- Inability to transition to baby food purees by 10 months of age

- Inability to accept any table food solids by 12 months of age

- Inability to transition from breast/bottle to a cup by 16 months

- Has not weaned off baby foods by 16 months

- An infant who cries and/or arches at most meals

- Family is fighting about food and feeding (i.e. meals are battles)

- Parent reports repeatedly that the child is difficult for everyone to feed

- Parental history of eating disorder, with a child not meeting weight goals

We are focusing on occupational therapy interventions for the purpose of this article; however, it is also common for speech-language pathologists to address feeding concerns, specifically as it relates to swallowing/choking/aspirating behaviors. It is important to coordinate with the child’s pediatrician to make sure referrals are made to appropriate specialists. Choking, gagging, vomiting, food coming out their nose, and aspiration during and after eating are very serious concerns and the child may need a swallow study or other assessment to check for anomalies.

The following case study highlights how Infant Mental Health and Occupational Therapy disciplines can work together to support the complex needs of infants and toddlers associated with picky and problem eating. That relationships are the foundation for all successful interventions was apparent through our work together.

Building an Alliance and Settling In

Lindsey — Infant mental health clinician

My work with Chloe and her family began when she was 10 months old, but the family had been involved with my organization for many years before that. Chloe lived with her mother, Sarah; father, Michael, and older brother. Chloe’s brother had been involved in the parent-infant program as a toddler and at age 5 had been diagnosed with autism. Because of that, Sarah was anxious about Chloe’s development and she was often very uncertain of her parenting skills. Sarah told me at our initial intake, “I don’t trust myself to know what is typical for kids anymore. How could I have missed the signs with her brother for so long?” The grief that comes with an autism diagnosis is often heavy and complex, and I often found myself supporting them during my four years of work with them. This was not the child she dreamed of having, and I needed to create space to validate her grief and to talk about the guilt she was feeling before she could move forward with possible interventions with Chloe.

The first two years of work with the family focused a lot on developmental guidance. Sarah and Michael looked forward to the completion of Ages and Stages Questionnaires to monitor Chloe’s development. Sarah continued to be anxious about Chloe, often worried that she would also be diagnosed with autism. For much of the first year of our work together, Chloe’s development was on track. It was into the second year that I began to notice that her language skills were mildly delayed, and our interventions and parent-child focused activities became geared toward supporting her language skills. Sarah and Michael were always very open to learning new ways to support her and would eagerly try to continue the activities outside of our sessions.

Along with developmental guidance, emotional support was a predominant core strategy used with Chloe’s parents to encourage their confidence and competence in raising their two children. During my weekly sessions, I would frequently observe the strengths they possessed as a family and notice them out loud. It was important to point out the moments of connection, as they were often difficult for Michael and Sarah to see. I wanted them to know how important they were to their children. Along with in-the-moment commenting, I would frequently use video in our sessions to observe strengths together and build upon them.

Sarah especially enjoyed doing art projects with the kids, and we would often videotape these delightful moments. Both Sarah and Michael had good insights into their children’s challenges, but they often felt frustrated and sad over not being sure how to help them. I often noted out loud how much I appreciated their willingness to be vulnerable. Sarah was very playful with her children and loved going out into the community and offering them experiences she did not have growing up. Both of Chloe’s parents had complex trauma histories, and as we got into the second year of our work together, we were able to explore more of the impact those histories had on their relationship with their children, each other, and their home environment.

The home environment was often very chaotic with little structure. The children did not have a consistent meal and bedtime routine, and we frequently focused on that during our sessions in those first two years. From the time Chloe started becoming independent in her feeding/eating, she would sit in a highchair on the floor in front of the TV. Additionally, because of her mild speech delay and observance of her brother’s challenging behavior, she frequently screamed to get her needs met. Chloe did not have a consistent meal schedule, which resulted in grazing; her family would feed her whenever she screamed. The family also did not typically eat a wide variety of foods, which limited what Chloe was offered.

Observation and Further Assessment

Lindsey

Around Chloe’s third birthday, Sarah and I started to become increasingly concerned about some of Chloe’s sensory processing issues and picky eating habits. It was something Sarah had brought to the attention of Chloe’s pediatrician on multiple occasions. Chloe frequently would scream when water was splashed in her face; she would not let her hair be brushed or washed so it was constantly matted, and she often refused to wear clothes. She had only 10 foods that she would eat, refusing to try anything new. Her food repertoire consisted of predominantly softer foods, with little variety. She would not eat foods of mixed textures (such as noodles with a meat sauce, instead the sauce had to be a plain marinara), she was very particular about meats (only cheeseburgers from McDonald’s, bologna and hot dogs), yogurt, one fruit and one vegetable. We would expect some pickiness or refusal to try some new items by the time a child is three, but we were not seeing Chloe eat many typical kid foods such as pizza, chicken nuggets, French fries, mac and cheese, etc. While she appeared to be a healthy weight (and trips to the pediatrician confirmed this), I was concerned that this would not be the case for much longer if her diet continued to be so limited. Mealtimes had consistently been a point of stress within the family at this point; Chloe frequently would have tantrums while Sarah would scream at the kids to just eat the food that was given to them.

Around this same time, I had hired an OT through a grant, which allowed both an OT and IMH clinician to go on home visits to work together.

I understood many of the behavioral and relational interventions that would support Chloe’s picky eating, but I began to realize that her needs were outside of my scope of practice and that she needed more intensive intervention from a specialist.

I referred Chloe and family to Deb for occupational therapy.

I was able to be present during Deb’s initial evaluation, as well as subsequent sessions, which allowed me to gain further understanding on how treatment would look. My initial reaction while observing the evaluation was feeling almost surprised by how much Deb was aware of, and in tune with, Sarah and Chloe’s relationship. I was struck by Deb’s ability to wonder about the parent-child relationship dynamics as she explored what the family’s relationship with food itself was like.

Through my work with Deb, I learned ways in which I could enhance what I already knew to support Chloe and her family. Deb and I quickly collaborated on how to support making mealtimes more enjoyable for Chloe and Sarah. Once again, we were able to successfully use videotaping to observe interactions and support these everyday routines. Deb helped me think about how the stress response system and appetite are directly linked together, which we were able to bring to Sarah and Michael during our sessions. The family was receptive to the information and the perspectives Deb and I brought them. Slowly, we began to see subtle improvements and more delight during meals.

Collaboration and Occupational Therapy Intervention

Deb

When I first met Chloe and Sarah, I noticed how Chloe was connected to and looked for her mother. In addition, I noticed how she called for her help when Sarah left the room and not as often with her father. During the evaluation, her mother was a strong participant and was encouraging to Chloe. Sarah had insights into the challenges her daughter was having but did not know how to help her. Their house had many activities and items that could support treatment, and Sarah was a willing participant in evaluation and subsequent treatment sessions.

When working with Chloe, it became evident quickly that she had not fully integrated her nervous system. This was evident by how she was still having difficulties engaging with activities and tasks of a variety of textures through her hands, without having negative reactions or atypical play with them. For example, Chloe was able to play with water through her hands but could not tolerate it splashing on her face. Also, she was slow to play with sand and paint. Initially, she would engage with one or two fingers for a few seconds and then over time she would add more fingers and play for longer periods. However, even between periods of play, she would wipe her hand or hands off. Most children at the age of three would dive in with both hands to get messy. They would not worry about cleaning their hands or be slow to touch either sand or paint textures. This type of engagement and play that Chloe demonstrated through her hands indicated that they were not integrated from a sensory perspective, which also meant her head and face were not as well, since the nervous system develops from feet to head. This meant we had to focus on integrating her nervous system before we were going to see change within the areas of grooming/hygiene, bathing, and feeding. I also had to change the environment and how some of these activities were being performed to create a new pattern since the current patterns were creating a stress response and negative reactions. This included changing the places activities occurred, who completed them, the tools used during the activity, and interactions/relationship between the parent and child. It also took recognizing sensory cues and learning to accept when a therapeutic break was required to then allow the task to be completed instead of just pushing through it.

This model assists across all areas of activities of daily living. A child will relax when you can create a secure and safe environment, which can then allow for growth and change. In addition,

we needed to try and create routine and expectations, which also create security and safety during tasks that children perceive as scary or that create a sense/state of anxiety.

This was the model used for Chloe’s feeding therapy, which combined sensory integration, transcending the food hierarchy model (Steps to Eating Hierarchy) with a variety of foods, modeling, environmental modification, and parent-child interaction modification. The sensory integration approach involved increasing exposure and tolerance to a variety of textures through her hands and slowly moving it up her arms toward her head and face, all while monitoring and respecting her interactions and need to clean up. A play approach was used for adding foods to her very limited repertoire by first increasing tolerance for being in the environment, to breaking it up and playing with it with tools, toys, and hands, then allowing foods to progress up her body till we could get it to her mouth, and then possibly taking a bite and spitting it out. These are activities we use to progress up the Steps to Eating Hierarchy. It is a therapeutic approach that allows for exposure to foods at a level of tolerance that a child can manage while learning about the properties of foods without the pressure of eating while working and addressing the different properties of new foods. It then progresses up to the mouth and eventually to eating a bit of a new food.

The education process around feeding is multifaceted and has many layers to create overall changes in feeding, the relationship between food and the person, the person and the environment, and the person and others within the environment, as well as changing current patterns, behaviors, and routines. For this client and her family, there was education about presentation of new foods even at the level of tolerating them in the environment or on her plate, creating a new routine around mealtimes. We worked with the family on establishing consistent times of day for eating because grazing behaviors do not promote a sense of hunger. We also wanted to encourage that at least one meal a day take place as a family. I noticed Lindsey exploring barriers to these two routines with Sarah and Michael, wanting to make sure they were as successful as possible. I could see how understood they felt by her, which led to more success and confidence in their ability to make these changes.

One of my top priorities was to move Chloe away from the TV, and instead to a table, in order to make food the most interesting thing happening at mealtimes. By decreasing distractions, we were able to promote the increased speed of eating, plus being around other people eating allowed for modeling and socialization of mealtime and eating behaviors. It also gave her the opportunity to be around new foods even if they were not on her plate.

There was a high degree of education, as well as emotional support provided by Lindsey and me, for Sarah to try and not worry during mealtimes. Often, Sarah was so concerned about what and how much Chloe was eating that Chloe’s stress rose during meals. Ultimately, we just needed her to eat. Kids pick up their parent’s stress and when the stress response rises it decreases appetite. This inadvertently creates a power struggle between the parent and child because the parent becomes focused on the child’s eating and then the child just exerts more control over the situation by not eating.

Lindsey’s knowledge of the family was integral in the development and implementation of all strategies and progress throughout the subsequent treatment sessions. Her in-depth knowledge of the family allowed for more realistic goals to be determined and for me to gain all relevant client factors that could help and impact progress. In addition, the relationship she had with both Chloe and Sarah created a sense of safety that allowed the client and her mother to be open to me and create progress within a very difficult area of feeding. Feeding is so multifaceted that it took the combined skills of Lindsey and me to make a true difference. I can impact the sensory processing, progress feeding, and create some environment and parent/child modifications, but Lindsey’s knowledge of the parent-child relationship was integral in changing those relationships to then allow the families to be available for my interventions.

“We don’t have to do it all alone. We were never meant to.” — Brene Brown

Lindsey

We wish we could say that all of Chloe’s feeding concerns were addressed by the time we finished working with this family, but just as parent-child relationship work takes time, so does occupational therapy and feeding treatment. Chloe made tremendous progress from a sensory integration standpoint, and she gained three new foods that she would consistently eat, and seven foods that she progressed up the Steps to Eating Hierarchy. Depending on when children ‘fall off’ the normal developmental feeding trajectory, it can take just as long to get back on track. Our work with this family highlighted the importance of professionals working together in collaboration and that we can’t do this work alone. Deb was able to support the family, and myself, in establishing new routines and attitudes around food, which created a building block, or planting of seeds, for us to take with us into our work long after she was gone.

References and Resources:

- Aviram et al (2015) Mealtime Dynamics in Child Feeding Disorder: The Role of Child Temperament, Parental Sense of Competence and Paternal Involvement. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 40(1). Pp. 45-54.

- Growing hands-on kids. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.growinghandsonkids.com

- Kranowitz, Carol Stock. The Out-of-Sync Child: Recognizing and Coping with Sensory Processing Disorder. New York: A Skylight Press Book/A Perigee Book, 2005.

- STAR Institute (n.d.) Retrieved from https://www.spdstar.org/

- Toomey, Kay & Ross, Erin. (2011). SOS approach to feeding. Perspectives on Swallowing and Swallowing Disorders (Dysphagia). 20. 82. 10.1044/sasd20.3.82.

**Steps to Feeding Hierarchy: This hierarchy represents the 32 steps it can take a person to eat one bite of a new food. It is a sequential desensitization approach created by Dr. Kay Toomey and is an evidenced-based approach to feeding therapy. It was established with a copy-write in 1995 (and updated in 2010). A person moves through the steps with interventions that provide them a safe environment along with the addition of other treatment strategies and theories. The major steps within the hierarchy are as follows: tolerates, interacts with, smells, touches, tastes, and eating. There are smaller steps within those larger steps, which progress upward from “tolerates” toward “eating,” and a person can start at any level for any food. After eating a single bite of a food, it can take up to about 30 trials of that food to determine if you like or dislike that food.