Sarah was an angelic-looking, bright-eyed four-year-old girl. She had a gleaming smile, immediate approaching behavior, and  exuberance, but she was exhausting to manage at home and in her preschool setting. Her parents contacted me because of her aggressive behavior and inability to control her impulses, her refusal to follow instructions and directions, and her lack of awareness of her physical strength. Sarah gave hugs like a “Mama Bear.” One of the first things that her mother said to me was, “She just doesn’t know how to be gentle! She’s like a bull in a china shop!”

exuberance, but she was exhausting to manage at home and in her preschool setting. Her parents contacted me because of her aggressive behavior and inability to control her impulses, her refusal to follow instructions and directions, and her lack of awareness of her physical strength. Sarah gave hugs like a “Mama Bear.” One of the first things that her mother said to me was, “She just doesn’t know how to be gentle! She’s like a bull in a china shop!”

They sought treatment so they can help her adapt to situations better and to get along with other children better. Her mother would like help because she feels worn down!

Historically, Sarah was a full-term infant weighing almost eight pounds and obtaining APGAR scores of 9 and 10 at one and five minutes respectively. During her first year the major problem was her recurrent ear infections; she was given ear tubes when she was two. Sarah was breast-fed for about eight months, and her mother recalled that her sucking response was like a vacuum cleaner! She had a “voracious” appetite. Her sleep pattern was not unusual, but when she awakened, even as an infant, she was active, alert, intense, and wearing on her mother. Mother described her husband as “a saint! He was and is the only one who can keep up with her!”

Sarah met developmental milestones on time; she began to present symptoms when she was about 2½. She had difficulty going along with family routines, was irritable, and very restless. She would get overly excited and was very difficult to calm down. Mother recalled that she was very sensitive to touch and would startle when she was touched. She began to display temper tantrums. Her over-excitability, restlessness, and tantrums have continued. She was described as one of the kids who goes from zero-to-sixty instantaneously. She had difficulty falling asleep and remaining asleep since she was about two. She never seemed to feel sleepy.

Sarah’s family included her eight-year-old and six-month-old sisters. Her parents, married 12 years, met in high school. They described their marital relationship as positive for both. They shared the childcare and they were both supportive of each other. Sarah’s mother was 35 years of age, her father 39. Both parents had college degrees and worked in the medical field. Sarah attended nursery school five days a week and was then cared for by a nanny — who had been consistent in her life — until her parents came home between five and six o’clock.

Mother stated that Sarah loved active, gross motor activities and had started a gymnastics class in which she was apparently doing well with the exception of having to be “corralled” to keep her in one place when she gets excited. She participated in all activities, but then want more and more when it is time to stop. She had boundless energy! Father commented on the fact that Sarah didn’t have an awareness of where her body stops and the next person’s body begins. She would run into people or objects and not feel pain, but when someone touched her, she over-reacted. Sarah also has displayed an interest in art and music and loves animals.

On an attention questionnaire, her parents indicated that she loses focus unless she is very interested in an activity. Her days are either excellent or poor with little “in-betweens.” She generally has difficulty finishing something that she starts. Her attention is variable as she “tunes in” and “tunes out.” Often, her attention is hard to attract and her work in school has an unpredictable quality. She can enjoy an activity one day and then the very next day she will reject the same activity.

Sarah was easily distracted by sounds and her parents felt that she did not attend to signals so she missed important information. She also was easily distracted by visual stimuli She craved excitement. Both parents agreed that she didn’t think before she acted; she did the first thing that came to her mind, and she did too many things too quickly. She had difficulty making friends and she tended to spend a lot of time by herself. Punishment did not seem to affect her and she made the same mistakes over and over again. Talking to her about her behavior had no effect in changing her. In school she seemed to treat other kids like they are objects, bumping into them and pushing them out of the way.

Sarah and her parents have been healthy, and there are no significant medical, mental health, or learning problems in her parents or extended family members.

According to the initial assessment process, several concerns presented by Sarah’s parents indicated that interoceptive awareness, or awareness of internal bodily signals, could be an area of challenge and warranted further investigation. Some of these reported concerns included:

| Reported Concern | Possible relation to interoceptive awareness |

| Sarah would get overly excited and had difficulty calming down. | This could indicate that Sarah was unaware of her bodily and emotional responses, thus leading to an inability to self-regulate (the ability to notice how one feels precedes the ability to manage the feelings). |

| Sarah was very sensitive to touch. Startled when she was touched.

|

Many of the skin fibers traditionally thought to be part of the tactile system are now found to be part of the interoceptive system. Interoception influences the experience of social and pleasurable touch. |

| Sarah has a high pain tolerance. She will run into people and not feel pain.

|

Pain signals are processed by the interoceptive system; therefore this atypical pain experience may reflect an interoception issue. |

| Sarah doesn’t know her own strength (giving bear hugs). She doesn’t know how to be gentle. She’s like a bull in a china shop. She has a lack of boundaries and does not seem to know where her body ends. | This could indicate a global poor body awareness, which is a skill influenced by the interoceptive sense.

|

| Sarah does not seem to know when she is emotionally overloaded.

|

Poor emotional awareness or understanding is a hallmark sign of poor interoception function. Interoceptive awareness provides the foundation of the emotional experience. The ability to notice and connect body signals to the meaning is what allows us to clearly identify what emotion we are experiencing. |

| Sarah is exhausting to manage at home. She still has a strong need for external controls.

|

This could indicate a lack of internal control caused by confusion or poor awareness of internal bodily (interoceptive) sensations. |

Intervention:

Due to the possible interoception challenges affecting Sarah’s ability to successfully self-regulate, incorporating interoception into the therapy process was deemed appropriate. The Interoception Curriculum: A Step-by-Step Framework for Developing Mindful Self-Regulation (Mahler, 2019) provided the guide for implementation of this work.

To start, the work focused on Sarah’s ability to notice body signals or to become more aware of her internal bodily experience.

As outlined in Section 1 of the curriculum, each week Sarah focused on one body part, spending time engaging in fun activities designed to evoke sensations within that one body part, giving her practice noticing and describing the way that body part felt. For example, during the first session (week 1), Sarah, along with the parent in attendance, focused on the hands and explored all of the different ways their hands could feel using concrete Focus Area Experiments (e.g., putting hands in cool water, touching an ice cube, squeezing a ball, holding a handwarmer, blowing on the back of the hand, etc.).

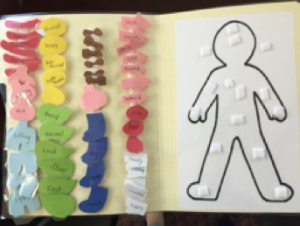

During the week, outside of the session, Sarah practiced noticing the way her hands felt during daily activities. She did this in two ways: Her parents would use IA on the Fly, which is a strategy where they used specific verbal prompts to ask Sarah how her hands were feeling. Sarah also practiced noticing body signals by completing Body Checks with her parents. This strategy uses a visual support that contains a body outline as well as body part icons that contain descriptor words she could use to describe the way each body part felt (see Picture 1). Sarah would complete the Body Check verbally with her mom or dad guiding her through noticing how her hands were feeling in that moment. Sarah’s parents also began completing their own Body Checks along with Sarah so that it became a structured activity that facilitated greater attachment and attunement.

Picture 1: Sarah’s Body Check Chart.

Sarah and her parents moved through this same process over the next few sessions (completing Focus Area Experiments during the session and Body Checks for positive practice during daily activities outside of the session), focusing on a different body part each week. The order of body parts, as listed in Table 2, moved from more concrete outer body parts to more abstract inside body parts. By the time she completed this process for eight out of 15 body parts included in the curriculum, Sarah was able to independently identify how each body part felt in the moment, using a wide range of age-appropriate descriptor language (due to her age, it was determined to focus on eight main body parts and her parents could use the same process to work on noticing body signals in more advanced body parts as Sarah matured).

| Week # | Body Part of Focus |

| Week 1 | Hands |

| Week 2 | Feet |

| Week 3 | Mouth |

| Week 4 | Eyes |

| Week 5 | Ears |

| Week 6 | Skin |

| Week 7 | Muscles |

| Week 8 | Lungs |

As Sarah and her parents participated in the lessons from Section 2 of the curriculum, they practiced connecting body signals to a variety of emotions. For example, Sarah discovered that when her muscles felt “jumpy,” that was a clue that she was really excited. Or when her mouth felt “dry,” that was a sign that she was thirsty. At home, parents were taught to use IA on the Fly (verbal prompts) to guide Sarah in connecting the body signals she noticed to the emotion (e.g., “Sarah, you said your eyes feel heavy. That is a great clue! What emotion could it mean?”) Wrapping up the curriculum with Section 3, Sarah was guided in discovering feel-good actions that helped her body feel comfortable.

Clinical reasoning behind The Interoception Curriculum

The Interoception Curriculum allowed Sarah to playfully gain understanding and control over body feelings via a systematic process. The work was thoughtfully chunked into small sections to make it manageable and not overwhelming (e.g., focusing on noticing body signals in one body part at a time). The process was predictable, which made it feel familiar and safe for Sarah and doable for her parents to incorporate into a busy family routine. Parents were involved in every step of the process, and focus was on empowering them to be able to support Sarah in developing clear body-emotion connections.

Therapy often focuses on regulation or coping strategies and fails to account for the underlying mechanism (interoception) that serves as the alert to use the strategies.

The process used with Sarah targeted the ability to notice and connect body signals, which served as her motivation to self-regulate.

Due to this focus, Sarah gained a sense of control over her body feelings and became a notably more confident and regulated child.

Implications for Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health

Interoception is intimately tied to the infant population, and the implications for infant mental health interventions are enormous. Infants do not have the language to articulate their inner experience, but they do have the “body language” to express themselves, e.g., crying, prolonged irritability, and moodiness. As the infant matures and develops language, if we ask the right questions, we can become attuned to the child’s experience. In our clinical work if we begin to ask: “How do you know you’re angry?” rather than “Why are you angry?” we may get a shrug or the response “I don’t know,” and find out that the child is not receiving the interoceptive signals of anger.

A young child with whom I worked stated, “I don’t feel anger until the moment before I explode.” All the mindfulness work that was attempted to help him calm down before he got too angry went nowhere because he was not receiving the signals. Other children tell us that they have lots of feelings, but they don’t know what they are because their interoceptive systems are not working efficiently and they cannot differentiate the signals. Interoceptive signals help us differentiate self from other, enabling the young child to recognize that feelings in an interaction belong to oneself or to the other.

Interoception is a critical variable in infant-parent psychotherapy and brings a new dimension into our clinical work. The concept of interoception is essential in parent and professional training. Our experiences as infants become embodied and can affect our psychological development years later. I had firsthand experience with a young adult who had had a very serious urinary surgery when she was 18 months old. She came into therapy in her early 20s suffering from agoraphobia. She slowly made her own associations to the experiences of being taken away from her parents in the hospital, experiencing what felt like assault by doctors, being placed in a bare room in a crib with slats that confined her and experiencing an intensity of lighting that, as an adult, was similar to the lights in a friend’s house where she couldn’t get herself to sleep. As she became re-connected to these late infancy experiences and made her own connection to these experiences, she made major gains in therapy. She was able to do things for which she had been paralyzed until she began to understand these connections.

If we help children get acquainted with their bodies from the beginning by helping them learn about sensations in each of their body parts, they begin to develop a sensations vocabulary and can tie these sensations together to develop an emotions vocabulary.

As children develop this awareness, with caregiver support they develop actions or strategies to deal with what they are experiencing. This has the possibility to decrease the number of children who develop early mood and disruptive behavior disorders. If we know what we are feeling and where we are feeling it, we can prevent and intervene to decrease arousal and help very young children develop neurophysiological modulation, sensorimotor modulation, control, self-control, and then self-regulation (Kopp, 1982). Our understanding of individual differences among children and the patterns of arousal in each individual child will enable us to develop the prevention and intervention tools that are currently limited at home, in school, and in clinical settings. This work is clearly cutting edge, and we still have a great deal to learn about it.

For further reading:

Craig, A.D. (2009) How do you feel-now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nature Review Neuroscience, 10, 59-70.

Critchley, H.D., Wiens, S., Rotshtein, P., Ohman, A., Dolan, R.J. (2004) Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nature Neuroscience, 7, 189-195.

Damasio, A. R. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: Picador.

Gilliam, Walter. “Pre–K Students Expelled at More Than Three Times the Rate of K–12 Students.” Yale News, 12 Sept. 2011, news.yale.edu/2005/05/17/pre-k-students-expelled-more-three-times-rate-k-12-students-0.

Fotopoulou, A. & Tsakiris, A. & Tsakiris, M (2017) Mentalizing homeostasis: The social origins of interoceptive inference. Neuropsychoanalysis, 19 (1), 3-28.

Kopp, C. (1982) The antecedents of self-regulation: A developmental perspective, Developmental Psychology,18 (2), 199-214.

Mahler, K. (2019) The Interoception Curriculum: A Step-by-Step Framework for Developing Mindful Self-Regulation

Oestergaard Hagelquist, J. (2015) The Mentalization Handbook London, UK: Karnac

Thompson, R. (1988) Emotion and self-regulation. In Thompson, R. (1988) Socioemotional Development, Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press.

Van der Kolk, B. (2015) The Body Keeps the Score. London, UK: Penguin Books.